Last week, the Board of Supervisors voted to override Mayor London Breed’s veto and passed legislation that will effectively downzone certain historic districts in the C-2 zoning district. According to […]

Last week, the Board of Supervisors voted to override Mayor London Breed’s veto and passed legislation that will effectively downzone certain historic districts in the C-2 zoning district. According to […]

The Mayor’s proposal to waive San Francisco’s Transfer Tax for certain converted residential space (“Measure C”) was approved by voters on March 5, according to the City of San Francisco’s […]

Earlier this month, the California Court of Appeal ruled that a qualifying development project in San Diego County could use the County’s General Plan Environmental Impact Report (“EIR”) to streamline […]

Two recent California court decisions, involving all-too-common neighbor disputes, have provided new guidance concerning easements and property ownership. In Romero v. Shih (S275023 [2024]), the California Supreme Court ruled that […]

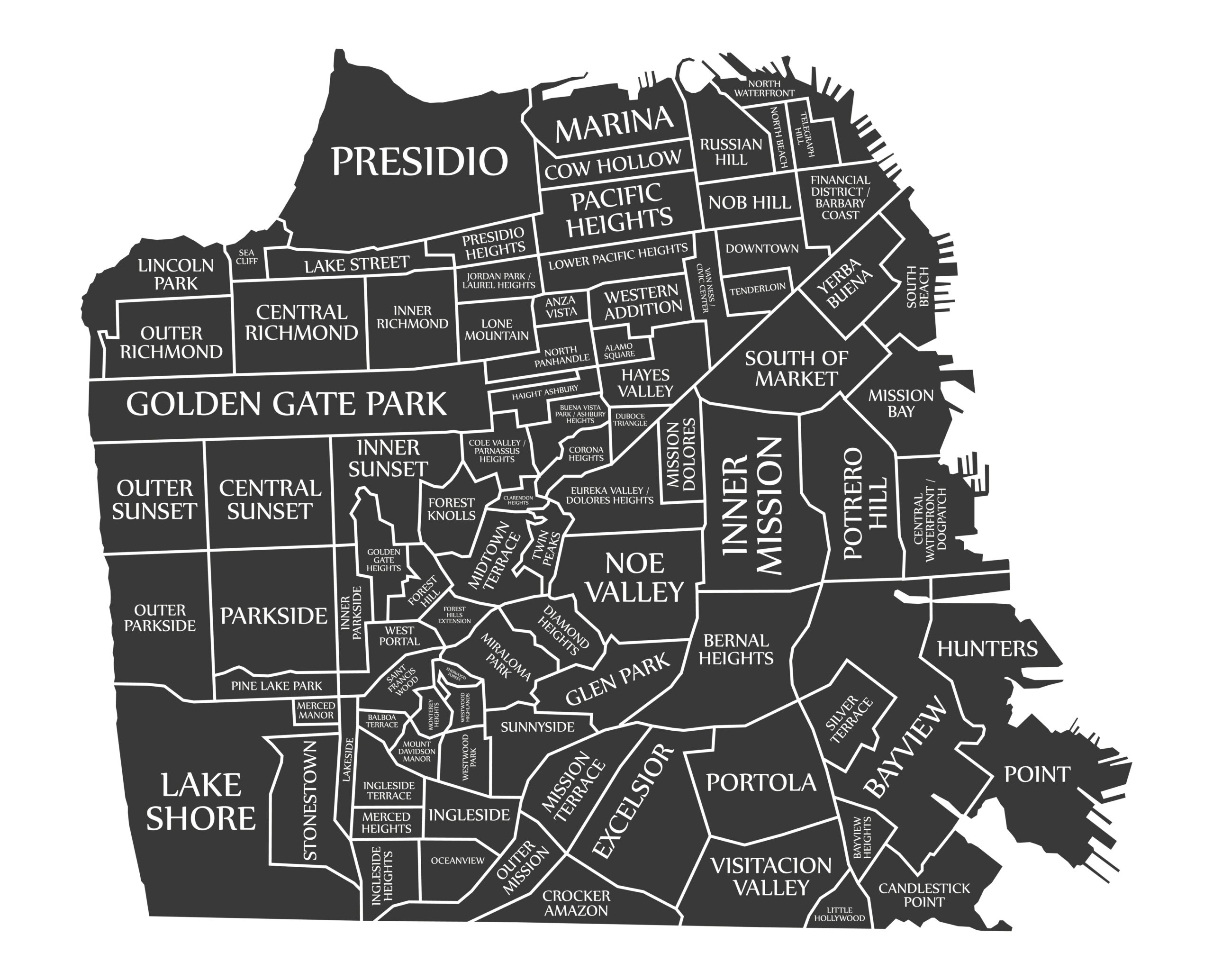

The San Francisco Planning Department has released more details on its Expanding Housing Choice Program, a citywide rezoning that will primarily target the city’s westside. The rezoning proposal originates in […]

Leases, construction contracts, easement agreements, and other contracts often require one party to name the other as an “additional insured” under its liability insurance policy. The insuring party often provides […]

The question has been previously raised – is a lease the same as a license – in that does the underlying occupant/user acquire tenancy rights by such occupation regardless of […]

We are following up on a previous update where we discussed Assembly Bill 572. After undergoing a few amendments in the State legislature, the Bill passed and became effective January […]

Can cities and states really ban natural gas hookups? On January 2, 2024, the Ninth Circuit handed down a decision in California Restaurant Association v. City of Berkeley finding that […]

Palo Alto recently reached a new housing milestone. On November 13, Palo Alto’s City Council adopted a legislative package implementing rezonings originally proposed in the City’s still uncertified sixth cycle […]